|

For some time now, seismograms have shown that earthquakes in the Himalaya mountains follow a seasonal cycle, with twice as many occurring in the winter (December through February) than in the summer. But those seismograms did not provide a reason for this seasonal variation of earthquakes. Now, using GPS (Global Positioning System) and GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) data, scientists at Caltech's Tectonics Observatory have figured out why.

The Ganges River Basin acts like a giant trampoline, sagging in summer under the force of the monsoons, rebounding in the dry winter. It is this rebounding action that gives earthquakes a little "kick." But how? Read on . . .

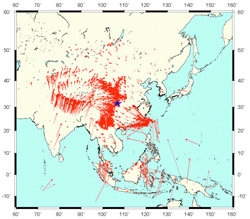

For the past 35 million years, India (or really the Indian tectonic plate) has been slowly and steadily continuing its 35-million-year-long collision with Eurasia, the land mass comprising Europe and Asia (see Figure 1). This collision compressed the two land masses, building the Himalaya mountains, which continue to rise (See animations in Figure 2).

However, upon close examination of recent GPS data, Tectonics Observatory scientists have discovered that the collision speed in the Himalayas (called the "rate of shortening," which can be also thought of as "squeezing") is not actually constant. Rather, in the Himalayas, the collision speeds up slightly in winter, and slows down in summer (see Figure 3).

Why would that part of the Indian Plate move faster in winter? The answer has to do with the monsoon rains. These great, annual rains swell the Ganges River, erode the hillsides and mountains, and bring sediment down into the Ganges River Basin, located just south of the Himalayas. This mixture of water and sediment weighs heavily on the Basin.

The land behaves much like a trampoline (see Figure 4). Imagine that the elastic material of the trampoline is the Indian Plate, with the center being the Ganges River basin. And image that one side of the metal frame is the Eurasian Plate. When water and sediments from the monsoon rains fill the basin, it is like a person stepping onto the trampoline. As the center of the trampoline stretches down, it pulls the material at the edge (northern India) down and back away from the frame (the Eurasian Plate), thus slowing the northern edge of India down on its relentless march to the north.

When the monsoons are over, the water leaves the basin. As the basin rises, its pull lessens, and so the northern part of the Indian Plate speeds up. This increased speed causes more compression in the Himalayas, which then triggers more earthquakes.

The speed reaches a maximum just before the following year's monsoons. It is at this time, just before the monsoons come, that the most earthquakes are seen to occur.

But what about the southern part of the Indian Plate? Figure 4 shows that the southern part of India is on the opposite side of the Ganges Basin. Again thinking of that basin as a trampoline, we would expect that in summer the southern part of India would be pulled forward, toward the center of the trampoline (the Ganges Basin), in the opposite direction from the way the the northern part was pulled, and thus speed up. GPS measurements have confirmed this result.

For more information about this seasonal cycle, see press release.

References

Bettinelli, P., Avouac, J.P., Flouzat, M., Bollinger, L., Ramillien, G., Rajaure, S., Sapkota, S., Seasonal variations of seismicity and geodetic strain in the Himalaya induced by surface hydrology, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2008 (pdf)

Bollinger, L., Perrier, F., Avouac, J.-P., Sapkota, S., Gautam, U., Tiwari, D.R., Seasonal modulation of seismicity in the Himalaya of Nepal, Geophysical Research Letters, 2007 (pdf)

|

Figure 1. Velocity of the earth's surface, from GPS data - Note India's northeasterly motion. Blue star indicates the 2008 China earthquake

|

| |

Animation:

Animation:

Continental Drift

|

Animation:

Animation:

Collision of India

|

Animation:

Mountain Building

|

Figure 2. Animations

|

| |

Figure 3. GPS time series data - showing that India speeds up in winter and slows down in summer

|

| |

Figure 4. The trampoline effect - a) A person standing on a trampoline pushes down on the trampline, which in turn pulls the frame down and back. b) Similarly, water and debris from the summer monsoons push down on the Ganges River Basin, which in turn pulls the Indian Plate down and back away from the Eurasian plate.

|

|